Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Alice Fraser, a comedian who works across Australia and the UK, says that what helps her feel safest in her work is when “somebody’s turned their mind to what it might be like to be me”. She offers a specific example: comedy venues and bookers suggesting a way to get home and even walking her to public transport.

The conversation about how to help women feel safe in Australian comedy has come to the fore following allegations of sexual assault against British comedian Russell Brand, allegations which he denies. Last week, a number of Australian women comedians spoke to this masthead about the local industry’s pervasive culture of harassment, abuse and sexual violence.

Comedian Alice Fraser always appreciates when bookers think about her needs before a show.

It’s a culture that is inflamed by unconventional, precarious working conditions, with comics working effectively as freelancers and performing mostly after dark in venues where alcohol and drugs may be present.

“The economics of this industry are built around 26-year-old boys who are happy to sleep on each other’s couches,” explains Fraser. “And if you’re not one of them, it’s not just that you don’t feel welcome, it’s that it is practically harder for you to do the job.”

These working conditions can be barriers to women’s participation in comedy. But there are potential solutions, including creating and enforcing a code of conduct, establishing a peak body, and setting minimum expectations for bookers.

“Comedy is one of very few industries that doesn’t have any peak body,” explains comedian Rose Callaghan. “So we have to manage everything ourselves. There’s no person or place to report things to … There needs to be a structured organisation that takes on the burden of this stuff.”

Rose Callaghan thinks there could be a case for a comedian’s guild in Australia.Credit: Alan Fang

These organisations exist in other industries and include the Australian Writers’ Guild and Actors Equity, while the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance union and Live Performance Australia advocate for performers but rarely delve into issues in the comedy scene.

Callaghan suggests that comedians, venues, management companies and others working in the industry could sign up to a guild and its code of conduct, with consequences for failing to adhere to its standards.

“Then everyone is acknowledging their responsibilities,” she says. “Comedians can be taken off a list of members of the guild if this organisation does an investigation and finds they have broken the code of conduct.”

There is precedent for setting up a professional comedy guild to advocate on behalf of comedians and resolve issues: comedians in New Zealand established a guild in 1999. The guild sets recommended pay rates, mediates professional disputes, and has created a code of conduct for people working in the comedy industry that outlines unacceptable behaviour.

The federal government’s newly created Creative Workplaces body may also provide oversight to the comedy industry. The body, which is in the process of being established, is expected to set workplace standards and codes of conduct across art forms, with the threat of government funding being pulled from organisations that fail to meet them.

In a statement, a spokesperson for Creative Australia said that Creative Workplaces will “promote fair, safe, and respectful workplaces for Australian artists, arts workers, and arts organisations”.

Fraser is unsure if comedians would be willing to sign up for a code of conduct: “When there’s been discussions about things like having a code of conduct in venues, [around] avoiding hate speech, there’s been furious arguments about that because comedians don’t like being told what to do.”

Instead, she suggests a structure of mediation and accountability. “Everyone would say their piece, and you could have a kind of community restoration process.”

“In Australia, you could call almost every venue in a few days and get an undertaking from them that if you blacklisted somebody, they would not put that person up,” she says. “But if you’re going to deprive someone of work, there needs to be an appeals process, a public process where somebody has a chance to defend themselves.”

In the immediate term, there are problems that could be addressed by individual bookers and comedy rooms. Scout Boxall, a comedian who was nominated for Best Newcomer at the Melbourne International Comedy Festival in 2021, also raises the point of getting to and from gigs safely.

It’s something that drew attention in 2018, when comedian Eurydice Dixon was killed on her way home from a gig in Melbourne.

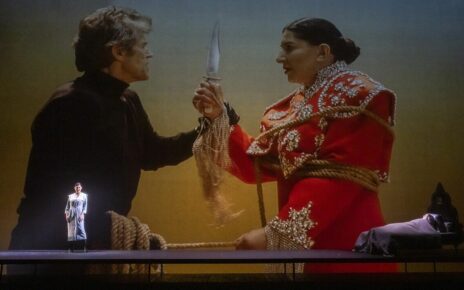

Scout Boxall suggests five things bookers could do to make rooms safer.Credit: Nick Robertson

Since 2019, MICF have organised and collected donations for Light the Way Home, an initiative that gives women, non-binary and other vulnerable performers free Uber rides during the festival, and to a limited extent throughout the year. In 2018, English comedian Angela Barnes established the UK equivalent, the Home Safe Collective, which runs during the Edinburgh Fringe.

“I don’t think, on an emotional level, men fully grasp the importance of stuff like Light the Way Home, of people car-pooling and offering each other lifts, of making sure people get home safe,” Boxall says.

Boxall’s suggestions for bookers, beyond helping acts to get home safe, is to find a venue that is as accessible as possible; pay comedians in food instead of drinks; and to circulate people’s pronouns ahead of time, which indicates that the space is safe for queer people.

“And if someone has a reputation, really think hard before booking them and think about who you’re also putting in that green room with them,” they say. “If you have to think super hard about putting someone on a line-up, you can just not put them on the line-up.”

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from books editor Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article