By Karl Quinn

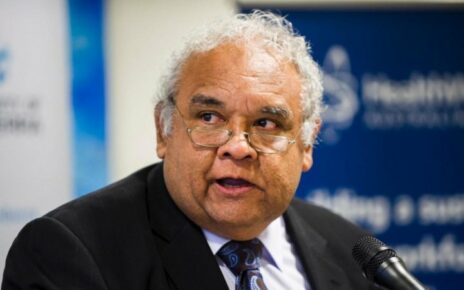

Anupam Sharma, director of Brand Bollywood Downunder, at his office in the Disney Studios complex in Sydney.Credit: Dion Georgopoulos

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

When the action-thriller Tiger 3 opens on Sunday to coincide with the Diwali festival of light, it will be on more than 160 screens – about one-twelfth of all the screens in the country. That will make it the biggest opening for any Indian film in Australia this year (though marginally smaller than RRR last year, which opened on 174).

Sure, it’s a long way short of the 873 screens on which Guardians of the Galaxy Vol 3 opened in May or the 765 given over to the year’s most successful film, Barbie, in July. But it’s comparable to the releases given to mid-market Hollywood fare like Dracula: Voyage of the Demeter (193 screens) and Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans (192), or arthouse movies with high expectations of becoming crossover hits, such as The Whale (154 screens) or Ego: The Michael Gudinski Story (181).

And it’s proof, if any were needed, that Indian movies are now a significant part of the Australian cinema landscape.

In his thoroughly engaging documentary Brand Bollywood Downunder, Anupam Sharma attempts to unravel the rather tangled connections between the Indian and Australian film businesses, on screen and off. He also goes much further, offering a pretty handy primer for audiences not overly familiar with India’s incredibly rich history of cinema. (Disclaimer: the author is one of Sharma’s interview subjects.)

“My ambition with this film had multiple layers,” says Sharma, who has been working in various capacities to build screen connections between Australia and India since the late 1990s. “One was simply me being fed up with everyone talking about Bollywood with a smile or a quizzical look, but not actually knowing about it.”

India is, he claims, “the biggest consuming and producing cinema population on the planet”. Its love affair with cinema goes back to the art form’s origins in the 1890s, and like early Hollywood, its quick take-up owed something to the way the medium – especially in its silent phase – could speak to vast numbers of people regardless of their literacy (or lack thereof) and the fact they did not share a common language.

Bollywood is often used as a catch-all term for any cinema from India, but that’s hugely reductive.

“Outside [in] the [wider] world, they call ‘Bollywood’ every film [from India],” says one of the filmmakers interviewed by Sharma.

“Nobody calls it ‘Polishwood’ or ‘Frenchwood’,” says another. “I hate it. It’s a borrowed term, and we are idiots to have accepted it.”

There are 28 states in India, 22 official languages, thousands of dialects, and many of those states and languages have spawned their own niche film cultures, each with their own nickname.

“There’s so many other cinemas – I think there are about 20 -ollywoods,” says Sharma. “But Bollywood has just caught on in the world.”

As well as Bollywood (films made by the Hindi-language studios based in and around Mumbai, formerly known as Bombay), which accounts for about a quarter of the 1500-2000 films made in India each year (and about one-third of the box office), there’s Tollywood (which confusingly refers both to Telugu-language films, which account for about 20 per cent of the box office, and to Bengali-language cinema), Pollywood (Punjabi), Kollywood (Tamil), Gollywood (Gujarati) and many others.

Regardless of where they come from, many films share the characteristics of what the wider world generally thinks of when the term Bollywood is used: chaotic plotting, colourful song and dance numbers popping up at seemingly random moments, and a somewhat circumspect approach to sex.

But by the same token, many do not. Just like the cinema of the West, India has arthouse productions, thrillers and action movies, and films that border on explicit when it comes to sex and violence.

And increasingly in Australia, they make good business. Indians and people of Indian heritage now comprise about 3.1 per cent of the Australian population, according to the 2021 census. But so far this year, films from India have accounted for about 4.4 per cent of the box office – a little over $33 million out of a total of just over $756 million.

In 2019, the last full year before COVID wrought havoc on the cinema business, 234 Indian films were released in Australia for a total box office of $29.5 million.

The Indian film market is, even more than the rest of the movie business, a numbers game. But those numbers paint a rather confusing picture.

RRR’s spectacular action and bold visual effects made it a huge hit in 2022, even beyond the normal audience for Indian films.Credit: Netflix

In terms of releases, Indian films are vastly over-represented, with almost one-third of the 600-odd titles released at the cinema this year coming from the sub-continent. But most of them are promoted only via social channels, play to discreet local and linguistic communities on just one or two screens, and do very little business at all (at least as far as the official box office reports are concerned).

Just 45 Indian titles have made more than $100,000 in Australia this year, and well over half of the 200-plus titles have taken less than $10,000. And yet, occasionally the numbers are genuinely big.

Thirteen of the 100 top-grossing films in Australia this year have been Indian, and so too are 26 of the next 100. Nine titles have taken more than $1 million this year. The biggest success, Pathaan, has taken $4.72 million, just ahead of Jawan, which has taken $4.68 million. They sit at number 35 and 36 on the ranking of films released since January 1.

Both were distributed by Mind Blowing Films, the company run by Mitu Bhowmick Lang, which has released 37 titles this year for a collective box office of $13.43 million, making it by far the biggest player in the space.

“When I released my first Indian film in 2002, it took $30,000 and I remember we were all so excited,” Lang says. “When I look at the growth of the audiences, and the fact second-generation Indians are bringing their non-Indian friends along to see our films with English subtitles, I just think the sky’s the limit.”

Lang is also the founder of the Indian Film Festival of Melbourne, which was last year awarded $3 million of state government funding over three years.

According to VicScreen’s annual report, at the 2022 edition of IFFM “162,000 people around Australia viewed more than 120 of the best films from the Indian subcontinent” live and online. By way of comparison, “approximately 140,000 Victorians took part”, online and in-person at the much higher profile Melbourne International Film Festival.

Lang is also a filmmaker, and received $2.2 million in funding from VicScreen, on whose board she sits, towards projects last financial year, including the portmanteau film My Melbourne.

The Victorian government is not alone in seeing value in aligning itself with Indian film, both as a way to connect with an increasingly important voter base and for the perceived economic benefits it offers. Virtually all the states have tried at one time or another to woo Indian filmmakers with incentives, and the federal government in March announced that it had signed a co-production treaty with India.

The Labor government claimed the Bilateral Audiovisual Co‑production Agreement would “encourage collaboration and creative exchange, leading to more Indian-Australian co-productions showcasing the best of both cultures, landscapes and people”.

For many, the term Bollywood conjures elaborate song and dance numbers that seem to erupt out of nowhere in the middle of a scene.

Arts minister Tony Burke and trade and tourism minister Don Farrell also revealed that the initiative would allow projects in both countries to gain access to government funding, including grants, loans and tax offsets.

In truth, the trade has always been bilateral. Indian filmmakers have been coming here since the 1980s, though their fast-and-furious approach to production has sometimes chafed against OHS- and application-obsessed local bureaucracies.

In the other direction, West Australian Mary Evans became one of Indian cinema’s biggest stars as Fearless Nadia, making 38 films between 1935 and 1968, despite remaining virtually unknown in her homeland until a belated discovery in the 1990s. And since the 1980s, Sharma says, Australian technicians – stuntmen, camera operators, even former cricketers such as Brett Lee – have been valued imports in the Indian film business.

In truth, Australia has often been more focused on the tourism, travel and education markets than the possibility of a filmic exchange. But with the growth of audiences locally, and the gradually increasing interest in Indian cinema from non-Indian viewers, that could be changing.

Indian cinema has a huge domestic audience, but it has long looked outwards too. Partly, that’s because of the enormous diaspora. But also, says Sharma, it’s because of a desperate desire to be taken seriously by non-Indians.

Salaam Namaste (2005) was reputedly the first Bollywood film made entirely in Australia.

“One of my favourite lines in the film is that Bollywood coming to Australia, to Europe, to other places was not about a wider audience but a whiter audience,” he says. “Because the colonial mindset always wants approval.”

And for an Australia that seeks entree to the vast market of India, what could be better than aligning with the stars?

“The only universal language there is cinema,” Sharma says. “If you want to promote yourself, all these major countries and brands use Bollywood actors as endorsements. As I say in the film, it was an arranged marriage, but a perfect one.”

Brand Bollywood Down Under is in select cinemas now.

Contact the author at [email protected], follow him on Facebook at karlquinnjournalist and on Twitter @karlkwin, and read more of his work here.

Find out the next TV, streaming series and movies to add to your must-sees. Get The Watchlist delivered every Thursday.

Most Viewed in Culture

Source: Read Full Article