Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Optometrists are warning of a myopia epidemic as the proportion of children presenting with short-sightedness almost doubles at some clinics.

The eye specialists believe children’s worsening eyesight is linked to genetics, excessive use of screens and not enough time outdoors.

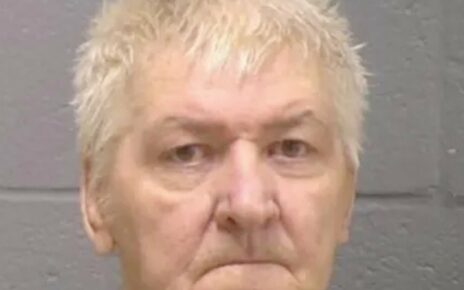

Jaelyn, Justyn and Jerryn Yam were diagnosed with myopia at the age of four. They wear special contact lenses at night to correct their sight during the day.Credit: Paul Jeffers

Zeinab Fakih, the Australian College of Optometry’s manager of paediatrics and rehabilitative service, said the average age of diagnosis had dropped from about 12 to eight.

She is concerned that some children are not being diagnosed until their eyesight has deteriorated to a level at which they are considered legally blind without glasses.

“We have a myopia epidemic,” she said.

Children who had been diagnosed with the condition at a younger age were more at risk of developing severe short-sightedness, which could cause blindness later in life, Fakih said.

The college’s Myopia Clinic in Melbourne has tripled the number of optometrists it employs to meet the surge in children presenting with short-sightedness.

More than 18 per cent of the children the clinic has seen this year have been diagnosed with myopia, compared with 10 per cent in 2021.

The public clinic has a waiting list of four months, which Fakih said was in line with similar clinics in New South Wales and Queensland.

She said many families were struggling to access and afford treatment to stabilise their children’s myopia.

Myopia presentations among children have also increased at Specsavers’ 387 stores across the country — 28 per cent of patients under 15 were diagnosed with the condition last year, compared with 22 per cent in 2016.

Specsavers’ head of professional services, Joe Paul, said he was particularly concerned about the increased prevalence of severe short-sightedness.

“These patients are at higher risk of blinding complications later in life, such as retinal detachments, myopic macular degeneration and glaucoma,” he said.

About 3 per cent of children presenting to Specsavers stores had severe short-sightedness last year, compared with 2 per cent five years earlier.

Shonit Jagmohan, an optometrist and director of Vision Camberwell Optometrists, said he was treating five-year-olds who could see only one metre ahead.

“If they were adults, they wouldn’t pass the driving standards,” he said.

There has been a 50 per cent increase in myopia presentations at his clinic over the past five years.

He said genetics and ethnicity played a role in determining whether a child would become short-sighted. The prevalence of myopia is twice as high among east Asians compared with Caucasians.

But he said the rise in short-sightedness across the world – the World Health Organisation estimates that 52 per cent of the global population will have myopia by 2050 – could not be explained by these factors alone.

Experts believe artificial light from digital devices and the proximity at which we hold them to our faces are contributing to the deterioration of people’s eyesight.

Another factor is not spending enough time outdoors. Studies have found that the intensity of outdoor light and the exposure of our peripheral vision to objects in the distance protect against developing myopia.

It has been speculated that the pandemic fuelled a rise in myopia cases among children because of reduced time outdoors and a sharp increase in screen time because of home-schooling.

There are treatments for slowing the progression of myopia: glasses, myopia-control contact lenses, atropine eye drops, low-level red light therapy and orthokeratology, which uses contact lenses to temporarily reshape the cornea overnight.

In the Yam household in Endeavour Hills in Melbourne’s south-east, Jaelyn, 13, Justyn, 11, and Jerryn, 8, were all diagnosed with myopia at the age of four.

“We thought maybe when they were six or seven they might need glasses, but we never thought it would be at four,” said their mother, Janice.

Initially, the children wore glasses but when they started school, they were fitted with orthokeratology lenses at Jagmohan’s clinic.

Janice said that after they wore the lenses overnight, her children had clear vision the following day and didn’t need to wear glasses or contacts.

It is hoped that after wearing the lenses throughout their adolescence, their myopia won’t progress.

“When I don’t wear glasses or contacts, I can’t see,” Janice said. “If my children can slow down their myopia, I’ll be happy.”

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article