Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Over the years, some of my friendships have withered and died, natural deaths caused by change and a narrowing of time, but I am thankful for those that have survived my growing old.

These friendships – childhood ones that are still alive, friendships with fellow journalists, and some more recent ones, miraculously recent because I thought new friendships would no longer happen to me, given my age – are no less a part of me than is my family.

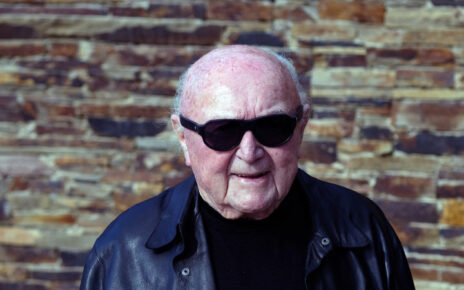

Former editor of The Age Michael Gawenda and publisher Louise Adler.

My friendship with Louise Adler did not wither with time. Our friendship was decades long, and it ended abruptly, but, looking back, I see that it had been unravelling for years.

I remember the date it ended. It was Saturday 9 October 2021, when I wrote to Louise and said I felt betrayed by her. It was Shabbes, the Sabbath, meant to be a day of rest, but we secular Jews do not follow every divine rule of Shabbes observance.

From the start of our friendship, the fact that we were Jews was important to both of us. Ours was a friendship that had started more than 30 years before, slowly at first, both of us taking small steps at a time, when Louise was arts editor of The Age and I was deputy editor. I think it was a difficult time for Louise, and I hope I was there for her, and not just because that was my role on the paper.

Part of my job was to listen, and try to smooth over – never fix, because fixing was impossible – the internecine conflicts between journalists and editors, and journalists and journalists, that are part of the fabric of most newsrooms.

Michael Gawenda in the middle of The Age newsroom in 1999.Credit: Age archives

When did we become friends? In my memory, it was some time in 1993, when Helen Demidenko won the Miles Franklin award for The Hand That Signed the Paper. Demidenko presented herself as a child of Ukrainian parents, and the main character in her book, she suggested at various times, was based on her grandfather, who was accused of being a Nazi during the war, a murderer of Jews.

The book tried to explain – if not quite justify – why this man had become a Nazi murderer. When it turned out that Demidenko was really Helen Darville, the daughter of English migrants, Louise was outraged; indeed, beside herself with rage.

We spent hours and hours talking about this hoax, about its meaning – not just, or even primarily, for Australian literature, but for Holocaust memory and the distortion of Holocaust history. How could a hoax like this be perpetrated, and how could a book like this win the Miles Franklin, our major literary prize?

We were furious together, over many cups of coffee. We were two outraged Jews – secular left-wing Jews, for whom the Holocaust and its remembrance and its lessons for humanity were to a large extent what being Jewish meant for us.

Louise did a lot for me. She encouraged me to write my first book and, what’s more, she published it. She encouraged me to write other books, some of which I did write and she published. But there was one book that she constantly urged me to write and that I did not write. It was a book about us, really, about our pasts.

We called it Jews and the Left – although, really, it was never going to be a dispassionate historical survey and contemporary analysis of the Jews and the left. For me, it was going to be about whether I had changed, drifted right, or whether the left had changed so that I no longer could easily say that I remained, without qualification, a Jew of the left. I do not think that is the book Louise had in mind.

We never talked about what our Jewish lives had become, even though that question sat there, like a serving of cholent on the table as we talked about our mothers and fathers and our children, and Holocaust literature, and films and Jewish food, and all the other easy stuff about being Jewish.

We did talk about harder things, too, personal things that I raise with some trepidation and will explore later. Both of us have close family members – Louise’s husband and my son-in-law – who are not Jewish.

According to the Orthodox religious definition of who is a Jew, both her husband and my son-in-law are fathers of Jewish children because the children’s mothers are Jewish. But if her son and my son married non-Jews, their children would not be considered Jews, no matter how Jewish their upbringing and no matter whether they identified as Jews. What does this mean for secular Jews like us? What does it mean if, like me, Louise believed in Jewish peoplehood and in Jewish continuity?

Michael Gawenda at the Wolfgang Sievers Human Rights Forum in 2008.Credit: Michael Clayton-Jones

Occasionally we did talk about Israel, and I told her that the increasing anti-Zionism in parts of the left made me feel that Jews like me were being cast out of our political home. I had not changed. I was – and remain – a social democrat, a person of the left.

But more and more of the left would banish me from the ranks of the comrades, because, in their view, anyone who does not support the dismantling of Israel, either by force or by international pressure, is a Zionist. This is a wildly ahistorical, and destructive, definition of Zionism, because it reduces complex issues of Jewish identity to ‘You’re either a Zionist Jew or an anti-Zionist Jew.’ That is the book I would have written – and perhaps I am writing it now.

We enjoyed ourselves when we were together. Although ours was not a transactional friendship, Louise did good things for me, and I hope I did good things for her, too.

I hope my support mattered to her when she was angry and sometimes despairing when she felt that some senior university bureaucrats, who had an oversight role of Melbourne University Publishing when she was its publisher, were treating her like a pushy Jewish woman. When she left Melbourne University Publishing in very trying circumstances, I abandoned a contract I had for a book with MUP because of the way she had been treated.

We remained two Jews drinking coffee and talking, talking, talking. How is it then that we did not talk about those things that would end our friendship? About the sort of Jews we had become, she and I, how each of us had changed, and what the changes might do to our friendship? About Israel – yes, it was about the way each of us thought and felt and worried about Israel, but it was about much more than that, because our feelings about Israel were, and remain, a sort of metaphor for the sort of Jews each of us had become.

Our friendship ended on Shabbes, on Saturday 9 October 2021, when I wrote to tell her that it was over.

Several months earlier, in the middle of 2021, Louise had commissioned and published a booklet by the then ABC senior news executive John Lyons. Dateline Jerusalem: journalism’s toughest assignment was the title.

At first, I thought it was meant to be a slightly humorous, wildly exaggerated title. It was not. Lyons meant it literally. His thesis was simple: the Israel Lobby in Australia had succeeded, through threats and accusations of anti-Semitism, in making cowards of Australian journalists and editors, who regularly self-censored their coverage of Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians. Journalists and editors were too afraid, too cowed by threats, to reveal the true horrors of Palestinian suffering at the hands of Israel.

Michael Gawenda’s new book.

The Lyons booklet was part of a public-policy series that Louise commissioned for Monash University Press. Just how the media coverage of the Israel-Palestinian conflict was a public-policy issue is hard to fathom.

The rest of the series were written by former politicians, or public-policy wonks. Good and worthy – and, it must be said, coming from the left – but these mostly sank without trace. Not so the Lyons booklet, which had nothing to do with public policy, but which she knew would get decent coverage – a journalist writing about the failings of fellow journalists and editors.

Although I was not named, and Lyons did not speak to me, I felt counted among those cowardly, intimidated editors. How could I not? I had been editor of The Age for seven years. I was editor when Bill Clinton’s failed peace initiative signalled the end of the Oslo process, which had provided a road map to a two-state solution to the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians.

I had been editor during the second intifada that followed Clinton’s failed peace initiative, when many hundreds of Israeli men, women, and children died in suicide bombings of buses and restaurants and community centres. Many hundreds of Palestinians also died in the IDF’s military response in the West Bank to the suicide bombings. What’s more, I was the only Jewish editor, back then and subsequently, of a major metropolitan paper in Australia. Why would Lyons not have spoken to me?

Louise knew all this, because we talked about it after she had commissioned the booklet but before it was published. She and I both knew what Lyons was going to argue. I was not named in the booklet and nor were the majority of the twenty-three editors and senior journalists that Lyons said he had interviewed on the record. They were anonymous.

I do not know how many of the anonymous editors that Lyons said he had spoken to confirm his thesis. In his booklet, he asks that he be taken at his word. Frankly, I am not prepared to do that. And nor should any journalist. This is what happens when your work is full of anonymous sources. Unnamed editors – how would any journalist agree to write a story like that? How many editors would publish such a story?

Oddly, the four editors he does name and quote in the booklet do not support his thesis. Two reject it outright, and one neither confirms nor denies it. Lyons quotes him as saying only that the Israel Lobby can be very aggressive and hard to deal with.

The editor refers to a particular meeting with a delegation from the lobby. The lobbyists had been rude and aggressive, and he had come close to throwing them out. Poor bloke. An editor being subjected to rude and aggressive behaviour! By a bunch of middle-aged Jews!

The fourth editor is Chris Mitchell, who was editor-in-chief of The Australian when Lyons was based in Jerusalem. Lyons does not ask Mitchell whether he was cowed by the Israel Lobby. He clearly felt no need to. After all, Lyons was one of the few Australian journalists, it seems, who resisted the brutal pressure of the lobby.

Did Louise ever wonder why Lyons did not speak to me, why I was not among those 23 editors and senior journalists he said he had spoken to? Did she not think it strange that he did not talk to me, given I had recently published a biography of Mark Leibler, one of the Israel Lobby’s senior people?

In The Powerbroker, I look at Leibler’s role as a leading player in the Israel Lobby. I examine in detail how the lobby operates, how it is financed, how it does its lobbying work. The Powerbroker was published by Monash University Publishing.

I had taken the book away from MUP when Louise resigned after pressure from the board. It had been a tough time for her, and I believed the board had behaved badly. She then took the book to Monash, where she was commissioning editor for the special series of booklets on public-policy issues, which included the Lyons booklet.

But when I wrote an article for The Age pointing out that Lyons had not spoken to me, nor named most of the editors who had spoken to him on the record, nor could he explain just why Jerusalem was the toughest gig in journalism – OK, I had a bit of fun with that – Louise wrote an angry piece for The Guardian accusing people who criticised Lyons – people like me, I assume – of cynically playing the anti-Semitism card. That clichéd straw man. Lyons’ straw man. And the straw man of virtually every anti-Zionist who is challenged by a Jew, Zionist or not.

Who called Lyons an anti-Semite? Who accused Louise of anti-Semitism? Why this response from her? Why did she commission Lyons to write about journalists and the Israel Lobby when she well knew what he was going to argue?

What he was going to argue was there in the letter Louise signed in May 2021– before she commissioned his booklet – during the conflict between Israel and Gaza. The letter was signed by 400 journalists and ‘media workers’ and replicated similar letters by journalists and media workers in other countries, including the United States.

It begins with a preamble that sets out the supposed facts – the truth about the Gaza war and about contemporary Israel, as well as its history. The facts, which the Australian journalists and media workers who signed the letter knew to be true, are these:

- Israel’s government, led by Benjamin Netanyahu, had unleashed an unprovoked, brutal war against the besieged population of Gaza.

- Seventy-five years after the Nakba – the expulsion by Israel of 750,000 Palestinians – Israel was maintaining an apartheid regime against Palestinians, both in the West Bank and Gaza and inside Israel.

- The only way to deal with this apartheid regime was ‘targeted sanctions against complicit Israeli individuals’.

The preamble ends with this:

″We believe the coverage of Palestine must be improved, that it should no longer prioritise the same discredited spokespeople and tired narratives and that new voices are urgently needed.″

Why wasn’t this just a little troubling to Louise, let alone to the journalists calling for the targeting with sanctions of ‘complicit Israeli individuals’. Who are these individuals that should be targeted? All Israelis who vote? Only those who voted for Netanyahu?

What about Israelis on the left who agree that Israel operates an apartheid system in the West Bank, but who reject the label when it comes to the treatment and rights of Israeli Palestinians? Perhaps all supporters of Israel – Zionists, Jews, and non-Jews alike – are complicit and should be targeted? Why only Israeli individuals? And what sort of sanctions exactly did Louise sign on to? Did she ask before she signed?

The journalists who signed these letters of course have every right to hold these views. But they do not have the right to state them as facts, as incontestable truths. Each one of their facts – their ‘truths’ – is contestable and contested. And not only by dreaded Zionists. It is disgraceful for journalists to state as facts or truths what is open to debate and contradiction. This is the road to fake news.

The letter then lists the actions that are needed to address the self-evident facts and truths of the preamble:

- Consciously and deliberately make space for Palestinian perspectives, prioritising the voices of those most affected by the violence.

- Avoid the ‘both-siderism’ that equates the victims of the military occupation with the instigators.

- Respect the rights of journalists and media workers to publicly and openly express personal solidarity with the Palestinian cause without penalty in their professional lives.

What this letter calls for, what it urges editors and executive producers to do, is refuse space and a voice to journalists and others who do not accept the black-and-white position of the signatories to this letter – that Israel is the villain that launches savage and unprovoked attacks on the Palestinian people in Gaza, on the powerless and the helpless victims of Israeli villainy.

And who exactly are ‘the same discredited spokespeople’ and peddlers of ‘tired narratives’, according to the signatories to this letter? I think both Louise and I know who they are. They are the ‘instigators of the occupation’ and their supporters, the Israel Lobbyists and their fellow travellers, the Zionists, most of whom happen to be Jews. And, I guess, those ‘both-siderism’ journalists, like me, who practise a form of journalism that does not see the world, and in particular the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, in Manichean terms.

But what most troubled me about that last paragraph was this. These journalists and media workers were demanding a wholesale abandonment of one of the central principles of journalism in a liberal democracy: the need for journalists to be independent, open, fair, and not agenda-driven in their work. That’s why they have the privilege and the freedom to report the world to us, why they play such a critical role in a liberal democracy.

Louise’s signing of this letter was the beginning of the end of our friendship. We arranged to meet so that we could discuss the letter face to face. If I am not mistaken, she did not much defend it when I pointed out why I believed it was so problematic, so wrong. She listened, and I thought she agreed with some of what I had to say. I think she respected the fact that I had spent a lifetime in journalism.

We did see each other one more time, when she told me she had commissioned John Lyons to write a booklet about the media and the Israel Lobby as part of the public-policy series she was commissioning. I was shocked. Stunned. Nothing I had said about the letter she signed had had any effect. Indeed, the letter had prompted her to get Lyons to write a booklet that would explain why journalists and editors had for so long promoted ‘tired narratives and discredited spokespeople’.

This idea that powerful Jews, through various means, but mostly involving wealth, have corrupted editors and journalists to stifle coverage of Israel’s appalling sins has been a staple of left-wing anti-Zionism for half a century or longer. These powerful Jews do this mostly by offering editors and journalists all-expenses-paid trips to Israel, where they stay – according to Lyons, who has gone on one of these trips – in the most luxurious hotels and drink the most expensive wines. Expensive booze! Devilishly smart, these Israel lobbyists.

That’s the soft power these Israel lobbyists employ to shut down coverage of Israel’s treatment of powerless Palestinians. How many editors or senior journalists, having stayed at superb hotels and having drunk gorgeous wine, could bring themselves to cover how Israel treats Palestinians? The hard power that the Israel Lobby employs consists of bullying and complaining, and more bullying and more whining, and more complaining. And threatening, of course, but threatening what – violence? damnation? cancellation? – is never clear.

Did Louise ever find this sort of stuff troubling? I thought she did, but perhaps I just assumed she did, because, really, it’s a fully blown conspiracy theory, isn’t it? Involving Jews.

The letter she signed and the booklet she commissioned by Lyons, what did that say about her and me, two secular Jews of the left? I think it said there was no longer the basis for any friendship between us.

When I started writing about all this, about the end of a friendship, I had planned to finish it, and that would be the end. But it turns out not to be the end. I have more to explore about the Jew I was, the Jew I am, and the Jew I am becoming. And what this means about my lifelong connection to the left.

This is an edited extract from My Life As A Jew by Michael Gawenda, published October 3 (Scribe, $35).

The Age has invited Louise Adler to respond to this extract.

Most Viewed in World

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article