When was the last time you saw bobbies on the beat in YOUR neighbourhood? WRITES FRED McMANUS

- Years of failed reform, political meddling and soft-touch justice have undermined policing, and left criminals unafraid of the law, argues this former Strathclyde officer

It was bitterly cold as I navigated icy pavements in the early hours of a winter morning – and spotted a figure shinnying up a drainpipe to a first-floor tenement window.

I was a beat bobby back then, checking the rear of some shop, and assumed the intrepid climber might have locked himself out, but called up to him: ‘What are you doing?’

With a degree of candour, if no sense of shame, he replied: ‘What do you think? I’m breaking in!’

The occupier of the flat had been asleep and was thankful he’d been alerted to the unexpected guest, who was arrested once he was safely back on the street.

In the 1970s and 1980s, when I was on the beat – later I was promoted to superintendent – these encounters didn’t happen every day, but it wasn’t unusual to come across a crime as it was being carried out.

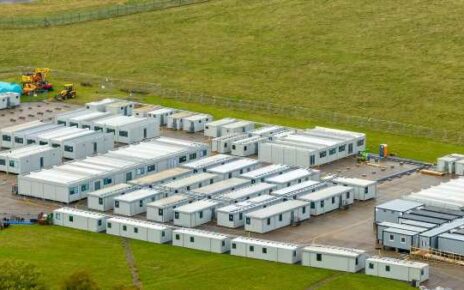

Beat retreat, Police patrols were once a familiar sight on Bonfire Night

Officers attacked in Niddrie with petrol bombs & fireworks, 5th November 2023

Today, police are effectively in retreat, having withdrawn from the communities they are supposed to protect, with stations shutting down and officer numbers at the lowest level since 2008.

It has helped to embolden criminals, and that loss of visibility has many repercussions, including the steady decline of respect and deference for policing.

If you grow up rarely seeing the police – except when things go seriously wrong – you will be wary of them, and that can and does build into resentment, fuelling an ‘us and them’ mentality.

One of my colleagues once told me there was a woman on his beat who sadly was regularly assaulted by her heavy-drinking husband and she was greatly reassured by the presence of a cop patrolling outside – her abuser, coming home from the pub, would think twice before attacking her.

These were vital relationships but they’ve been swept away over the years so that beat policing is more or less extinct, allowing thugs and thieves to commit crimes without fearing the consequences.

Last month Justice Secretary Angela Constance claimed the youths who attacked riot police with fireworks and petrol bombs on Bonfire Night were ‘vulnerable’ and ‘disengaged’ from society.

The worst disorder took place in Niddrie in Edinburgh, where more than 100 youths targeted police amid ‘unprecedented levels of violence’.

In the weeks that followed, officers tracked down some of those responsible using video footage taken by specialist evidence-gathering teams.

Police say they lack the manpower to make arrests at the time of such incidents – now depressingly frequent – but clearly they had the personnel on hand to film officers coming under attack.

The prevailing theory is that officers weighing in to put handcuffs on these yobs would inflame the situation, but swift ‘nip in the bud’ arrests can sometimes stop escalation, laying down a marker for others who might be tempted to join in.

In Greenock, I was called to a report of public disorder and we found a group of 40 or so youths – or neds, as they were called at the time – most of whom scattered when our unmarked car pulled up.

One of them was armed with a stick and I gave chase.

Eventually he ran into a tenement close and when I opened the door he lashed out and caught me just under my eye; the resulting injury required five or six stitches but I got hold of him and he was arrested.

On another occasion, there was a report of ‘group disorder’ in Paisley – gang fights were commonplace.

I chased one of those involved for a quarter of a mile, then as I was about to run round a corner I saw a shadow.

He was lying in wait for me and I could see in the street light he was holding a big pole – ready to bring it crashing down on me.

I crept up alongside the wall and reached round with my baton, hitting out at him and catching him, as it turned out, in the face, before apprehending him.

Naturally, he complained but he was given short shrift – we weren’t as well protected as officers are now, with Taser stun-guns and pepper spray – though it’s shameful that Police Scotland, unlike English forces, hasn’t yet equipped cops with body-worn video cameras.

But the bosses usually had our backs.

There is an inquest culture now, with the balance skewed towards the rights, or supposed rights, of criminals, so today I might have found myself subject to a disciplinary hearing for tackling that pole-wielding ned – even if doing so possibly saved my life.

The intelligence about gang conflict and public disorder came from the beat cops – and it was clear in Niddrie that police were blindsided by their attackers because they hadn’t picked up on signs of trouble brewing.

Police Scotland, created in 2013, was an attempt to impose a one-size-fits-all approach on the whole of Scotland but it was bound to fail.

Officers’ links with local communities were severed, and the policing needs of the islands, for example, will be very different from those for the centre of Glasgow and Edinburgh.

The single force was intended to cut costs, yet it limps on in a state of seemingly permanent financial crisis.

Inevitably, it has fallen prey to politicisation – something that was far harder when there were eight chiefs under the previous territorial model, and they were generally charismatic people with a sense of authority.

In the 1980s, I accompanied Sir Patrick Hamill, boss of the now-defunct Strathclyde Police – my former force – to a council committee which allocated funds to police and fire services.

He was told his budget would be cut by millions and he calmly responded that this would be possible – but he’d have to close police stations in Milngavie and other well-off areas, which would be sure to trigger a backlash.

The committee backed down.

Those chiefs were old-fashioned cops who wouldn’t be pushed around. It’s far less clear that this is the case with Police Scotland, which has become a political football.

Senior cops who run the force now may have had no meaningful experience of having been on the beat and they advocate a different tactic – trying to anticipate demand and hopefully being in the right place at the right time.

This is reinventing the wheel – I recall similar strategies decades ago when we were told research had suggested crime was more likely to happen late at night between town or city centres and housing estates, as people made their way home from pubs and clubs.

For most beat cops, that wasn’t exactly a surprise.

Trendy academic thinking of this kind – known as intelligence-led policing – put paid to beat policing about 20 years ago and officers effectively disappeared from many neighbourhoods – when was the last time you saw a bobby on patrol on your street?

It is certainly true that, with only 16,600 officers, police nowadays have to prioritise – but cutbacks can be counterproductive.

I set up a vehicle theft unit in the north of Glasgow in the late 1990s which collared 350 car thieves in one year.

There was an officer collating intelligence gathered by beat cops, and a dog-handler was attached to the unit to help pursue runaway thieves.

It was successful but the unit was scrapped after a change of management – and it’s hard to imagine any such initiative now, given the major financial constraints police face, with one top Police Scotland official recently admitting ‘every penny is a prisoner’.

But there are many false economies.

On the night in October when the new chief constable, Jo Farrell, took her infamous taxpayer-funded ‘taxi ride’ south of the Border to her family home, after stormy weather forced the cancellation of her train, it emerged that her chauffeur was a traffic cop – one of only two covering Lothian and the Borders.

That’s scandalous – in north Glasgow there would have been 20 to 30 traffic officers under my command on any one shift. How much crime is now going undetected?

We’re in an absurd situation where police are refusing to investigate crime deemed to be minor – as happened in a recent pilot project in the North-East.

It is now under evaluation pending a potential wider roll-out.

At Strathclyde Police, we always looked into reports of crime, or tried to listen to people’s concerns, even if they didn’t amount to a report of a crime – and the notion of ignoring them wouldn’t have occurred to us.

That said, there is no doubt that helping people who pose a risk to themselves or others, because of mental health problems, puts huge pressure on police.

Forces in England and Wales have laid out plans to reduce the number of mental health callouts to which they will respond.

Under a new framework, known as the National Partnership Agreement, some forces will attend only 20-30 per cent of health and social care incidents in the next two years.

In Scotland, thankfully, this has been resisted so far – protecting the public is a core legal duty of policing – but rank-and-file officers rightly point out that about 80 per cent of incidents attended by police north of the Border do not involve a crime.

Up to 60 per cent of an officer’s shift can be taken up by mental health incidents because they’re held up in hospitals, trying to get the vulnerable person admitted – a process that needs to be accelerated.

It’s wrong to propose simply ignoring these calls – it’s easy to imagine someone tragically taking their own life, or taking someone else’s, when police don’t turn up.

Meanwhile, thousands of homes across Scotland have been declared ‘too dangerous’ for ambulance crews to attend without police back-up – another burden on the force.

Many cops are doing a brilliant job against all the odds but they are being let down by top brass and our political masters, and an increasingly soft-touch justice system.

We desperately need effective sanctions – and that is proving a problem as the courts are yoked to sentencing guidelines urging leniency for under-25s due to the alleged immaturity of their brains.

Given that most of the vicious louts who spent their Sunday evening launching petrol bombs at police in Niddrie are likely to be under 25, they have little to fear from the courts.

It’s obscene, given that in their mid-twenties some criminals are reaching their prime, and young offenders aren’t as naive as they used to be.

Recorded Police Warnings are regarded as a joke by those who receive them – and they are now dished out even to people caught with hard drugs.

Police Scotland cannot or will not say how many have been issued to those found in possession of cocaine and heroin – Class A substances which have fuelled Scotland’s drug deaths crisis, the worst in Europe.

Crime is being kept off the books, allowing ministers to boast about a fall in offending – but the Scottish Crime and Justice Survey (SCJS) recently revealed record levels of violent crime, theft and vandalism are not being reported because the public have no confidence that officers will respond.

It’s no wonder people are giving up on the police, given that they’re so hard to contact – and when you do get in touch they might say they can’t help because they don’t have the resources or because they have a policy of not investigating less serious offences.

But criminals are quickly getting the message that the police aren’t to be taken seriously.

The SCJS also found that only 39 per cent of those asked said they were aware of regular patrols in their area.

True, cyber-crime in all of its forms – from fraud to grooming and online child abuse – is a growing problem and takes cops away from the front line.

The police must respond accordingly – and get the funding they need for that purpose.

But that doesn’t necessitate the loss of beat policing, which in reality no longer happens in any meaningful fashion.

Police need to get back to basics and back out on the streets – and if that is too upsetting for the Lefty do-gooders, in government or at the top of Police Scotland, then I’m sure that the majority of law-abiding folk will say: ‘Too bad.’

Source: Read Full Article